An Open Ecosystem

Linux is an open-source community that focuses on sharing power and responsibility among people instead of centralizing within a select group. The Linux kernel – which acts as the foundation for many Linux-based distributions – is built on an even older framework that matured alongside computers.

The PDP-7 ran the first Unix code – used for creating the demo video game Space Travel.

|

|

An Accidental Movement

Unix was a general-purpose operating system that began to take shape in the mid-1960s. This was a collaborative project between the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Bell Labs, and General Electric. Academic researchers within the burgeoning computer science field experimented with the potential for time-sharing to innovate what was possible with these new digital machines.

Unix itself was based on an even older exploration in computers – an operating system called Multics. Pronounced as "eunuchs", the name itself was intended as a pun on it's predecessor. Multics had yielded truly innovative ideas, but it's exploratory nature wasn't immediately profitable and the project was eventually

shuttered.

What we wanted to preserve was not just a good environment in which to do programming, but a system around which a fellowship could form. We knew from experience that the essence of communal computing, as supplied by remote-access, time-shared machines, is not just to type programs into a terminal instead of a keypunch, but to encourage close communication.

— Dennis Richie, UNIX pioneer

The original AT&T Unix – created in 1969 – was a proprietary and closed-source operating system first investigated by Bell Labs. As the result of a result of a 1958 ruling by the US Department of Justice, AT&T was forbidden from entering into the computer business under consent decree. This was a part of the larger breakup of the Bell systems that continued through the 1980s.

This meant that AT&T was required to license it's non-telephone technology to anyone that asked. While Unix was intended for use within their labs, they began licensing it to colleges and corporations for a modest fee. This lenient licensing scheme played an important part in the widespread adoption of Unix and the eventual open-source movement.

Cathedral and the Bazaar

During the early days of computers, programmers and researchers were one and the same. While developing programming languages like C – the backbone of Unix – we were also exploring what computers could accomplish for the first time. To that end, it was common to share software and learn from each other while studying computing.

Cathedral and the Bazaar was a foundational book by Eric S. Raymond about opposing software project management styles.

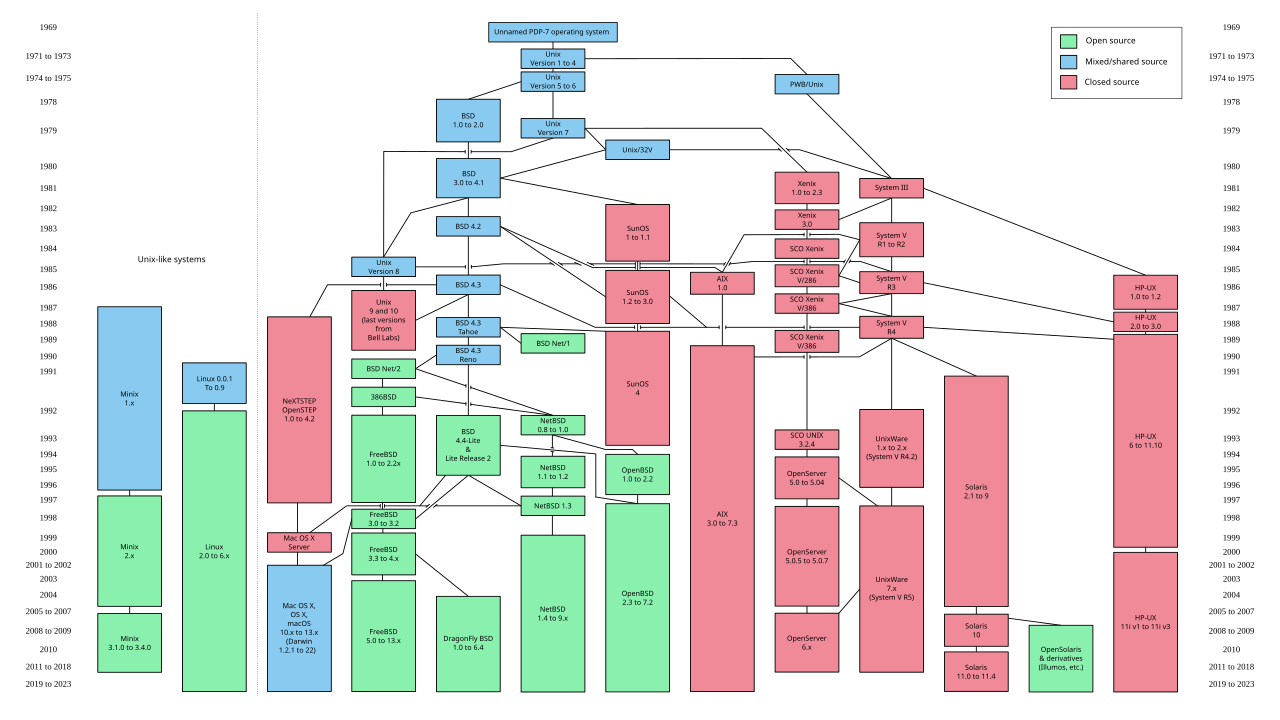

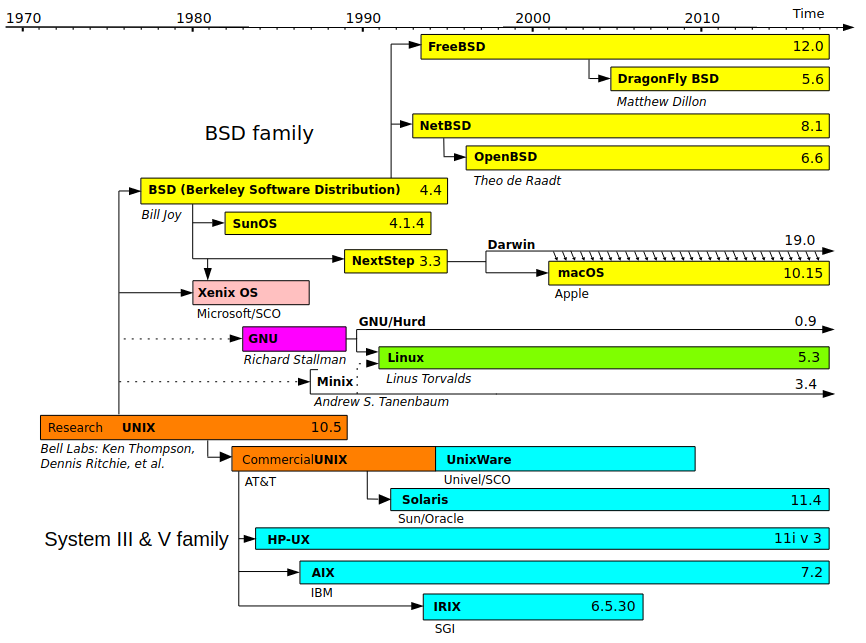

Unix was revolutionary not only as an operating system, but because it came bundled with a complete copy of the source code used to build it. This allowed researchers to modify the code to fulfill their needs while also enabling corporations to create their own custom Unix distributions – for use in-house or as a marketable product. This led to a proliferation of Unix operating systems, each with exciting new features.

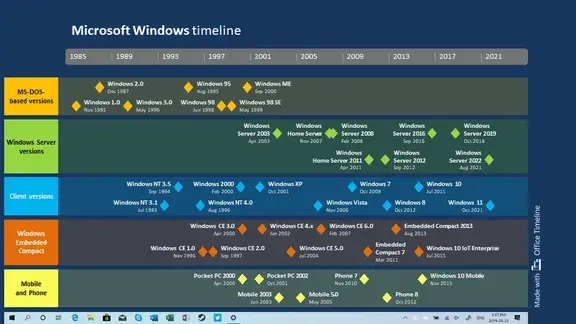

Windows vs Mac vs Linux vs Unix timeline graphic

Software – like hardware – became increasingly commercialized throughout the 1970s. Corporations sought to mold hardware into compact personal devices while simultaneously fashioning software into the killer application that would draw consumers to their products. The Unix Wars throughout the 1980s exacerbated the friction between vendors as the operating system became fragmented between multiple competing standards.

This 'release late—release rarely' philosophy arises when the software developers regard their project as a consumer product. While the product is marketed towards consumers, their role in the creative process is rather limited. Their feedback is often collected reactively during formative beta testing – or even after the product is released to the public.

Proprietary software is often "closed-source", meaning that the code to create it is private and legally protected – or even a trade secret. The code is compiled into a binary file containing the raw binary data – ones and zeros – used to control a computer system. This data it is not human-readable and only works on a specific platform – such as Windows, MacOS or Debian Linux.

This makes it relatively difficult to reverse engineer, but it also means that the code wasn't compiled to run efficiently on your specific computer system. Instead, it is compiled to meet 'minimum system requirements' and more advanced hardware is rarely leveraged to your advantage.

Software Freedoms

During the 1970s, the original computer hacker culture – who enjoyed the creative challenge of overcoming hardware and software limitations – formed within academic institutions.

It was around this time that the Free Software Movement began to take shape. Researchers continued to develop software collaboratively by sharing their discoveries and the source code that powered them. This was foundational to the continued growth of the Unix experiment.

In 1984, Richard Stallman resigned from his position at MIT citing that proprietary software stifled collaboration by limiting his labs ability to share source code. He began work on the GNU Project – which stands for GNU's Not Unix – and represented an idealized ,"free" operating system. It behaved almost exactly like Unix to attract developers, but the source code would be available for anyone to modify.

The word "free" in our name does not refer to price; it refers to freedom. First, the freedom to copy a program and redistribute it to your neighbors, so that they can use it as well as you. Second, the freedom to change a program, so that you can control it instead of it controlling you; for this, the source code must be made available to you.

The Free Software Foundation he sparked – through his call-to-action known as the GNU Manifesto – initially caused some confusion. He often had to explain that he meant "free" as in "freedom" not as in "beer". This led to the foundation of the movement: the four software freedoms.

|

Counter_1 |

Freedom 1 The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose.

|

| Counter_2 |

Freedom 2 The freedom to study how the program works, and change it so it does your computing as you wish.

|

| Counter_3 |

Freedom 3 The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor.

|

| Counter_4 |

Freedom 4 The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others. By doing this you can give the whole community a chance to benefit from your changes. |

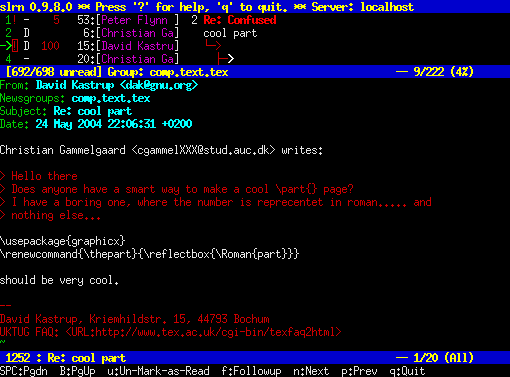

Fulfilling these freedoms required unrestricted access to the underlying source code. Through GNU, a new decentralized model of development emerged that enabled everyone to contribute bug fixes, code suggestions and feature requests. Communication took place primarily on internet newsgroups like Usenet – one of the first examples of a public-facing digital bulletin board.

GNU developed in sharp contrast to proprietary software with many open-source projects following the 'release early—release often' development philosophy. These software programs are not generally viewed as a consumer product, but as a tool to reach an end.

While these projects may feel less polished, users have the power to add their voice throughout the entire development process. This means the potential for bugs to be fixed promptly and – depending on community feedback – features can be quickly integrated into the ongoing evolution.

The GNU Project is an umbrella for the hundreds of smaller projects that are necessary to build an operating system from the ground up. While developed through collaboration, these constituent projects are produced independently of the others.

Modular by Design

While lying the foundations for Unix, computer scientists were careful to consider it's design philosophy. They decided that Unix should provide a simple set of tools – each able to perform a limited function with well-defined parameters. This facilitated a modular and decentralized approach to developing the new operating system.

This philosophy disconnected the lifecycle of applications from each other – as well as from the operating system. This led to a rolling release model where individual software packages were updated frequently and released quickly. These modular programs could be maintained independently and development teams only needed to coordinate how their modules would communicate – such as a mutually-defined API or the system call interface.

Software was specifically crafted to fill an empty technological niche and fulfill a desired goal. Communities formed to compare and contrast methods for reaching the same end. Developers held the autonomy to make their own decisions about how the project would progress.

After using a high-level programming language to code a software program, it needs to be translated into machine code. This creates the executable program to can communicate with your underlying hardware through your operating system. This process happens in multiple stages – some well in advance, while others happen just-in-time.

((Diagram showing compilation happening in stages, including object code, machine code and just in time))

The Windows operating system revolves around compiled programs that are easy-to-use and operate. Similarly, Linux provides access to compiled software out of the box, but also provides the source code for anyone to compile software from the ground up for their specific hardware. In practice, this can bring new life into even the oldest computer systems.

Licensing

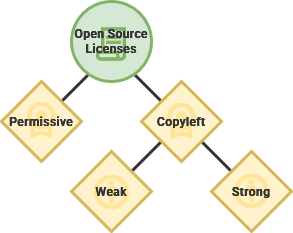

Copyright grants exclusive legal rights to the originator of a creative and intellectual work – like a book, movie or software code. Relatedly, copyleft is a philosophy that leverages the legal protections of copyright to prioritizing sharing and collaboration.

Starting in 1985, GNU Software was released under the GNU General Public License and enabled full use by anyone – with specific restrictions. This was the first copyleft license mandating that all derivative works maintain reciprocity.

Copyleft Licenses

There are a spectrum of requirements for fulfilling the developer's intended spirit of reciprocity – from maintaining a similar software license to simply attributing through a file.

While modern "weak" copyleft licenses allow embedding within proprietary projects, the original "strong" GPL license required that the derivative project retain the same license.

|

|

Copyleft Licenses |

|

License |

1989 A strong copyleft license that comes with many conditions for usage within derivative software while providing express consent to use related patents.

|

| License |

2010 This license foregoes intellectual copyright and attributes all work to the public domain. While not technically copyleft, this anti-copyright license is compatible with the GNU GPL.

|

| License |

2012 This license balances the concerns of free software proponents and proprietary software developers.

|

By 1989, University of California, Berkeley introduced BSD – or the Berkeley Software Distribution – and created the first publicly accessible Unix operating system. By rewriting proprietary AT&T Unix code from the ground up, they released BSD to facilitate open collaboration.

They created their own permissive software license that placed barely any restrictions on how you could use the software. This also provided no warranty about the continues maintenance of the project and removed the developers from all liability. This even explicitly allowed proprietization – meaning it could be used within private, "closed-source" programs.

Permissive Licenses

One of the primary differences between a copyleft license and a permissive license is the concept of "share-alike" – which relates to the Creative Commons.

Copyleft licenses require that information about the original work is available, often creating a web of interconnected projects. Permissive licenses, on the other hand, have few stipulations on how they can be used.

|

|

Permissive Licenses |

|

License |

2004 A permissive license that allows that this software can be incorporated into larger projects that themselves are released under a different license.

|

| License |

1987 This straightforward license only requires that the licensing information is shown, otherwise the software can be used freely for any reason.

|

| License |

1990 The first in a family of permissive licenses with the original requiring acknowledgement in the advertisement of all derivative works.

|

Free – or Open?

During the early 1990s, the GNU Project proceeded until it neared completion – the only thing it was missing was a kernel. This integral system handles all interactions between software and hardware within a computer system. Without it, the operating system wouldn't even be able to operate. Their free kernel – known as GNU Hurd – was still incomplete.

Linus Torvalds, operating independently of the GNU Project, created the first version of the Linux kernel during his time as a computer science student. He released the software under the General Public License. This meant the software could be shared freely and modified by anyone.

GNU adopted the new Linux kernel as its own – which was now rapidly evolving into a global community. The resulting operating system is now known most commonly as Linux – even though there is a movement to change this to GNU/Linux. Many Linux Distributions use the Linux Kernel by default.

At a conference, a collective of software developers concluded that the Free Software Movement's social activism was not appealing to companies. The group – later known as the Open Source Initiative – felt that more emphasis was needed the business potential of open-source software. Linux was quickly adopted as the flag-ship project of the newly forming Open-Source Movement.

Compared to the earlier Free Software Movement, this new initiative took less of a focus on social, moral and ethical issues – like software freedom and social responsibility. Instead, the open-source movement chose to highlight the quality, flexibility and innovation that could be accomplished by sharing access to source code. In practice, this meant focusing on creating "something more amenable to commercial business use".

Social Contract

By creating mechanisms to decentralize software development and focusing on discrete modules, Linux began to produce viable operating systems. The process was not always easy or direct, there was often difficulty with navigating divide – both geographical and interpersonal. The Linux – and larger computing – experiments have produced some notably strong personalities.

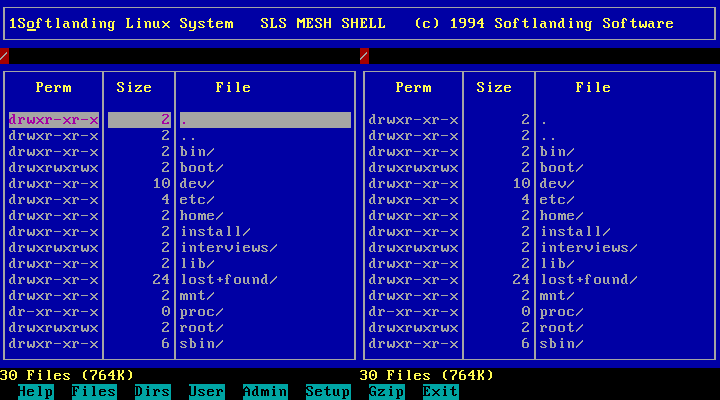

The Linux project quickly ballooned to over a hundred developers. Combined with software from the GNU Project and other developers, complete Linux operating systems began to conglomerate. During 1992, SLS – or Softlanding Linux System – was one of the first virally adopted distributions. Roughly patched together with a rudimentary interface, it was riddles with bugs and was notoriously difficult to use.

Defining Simplicity

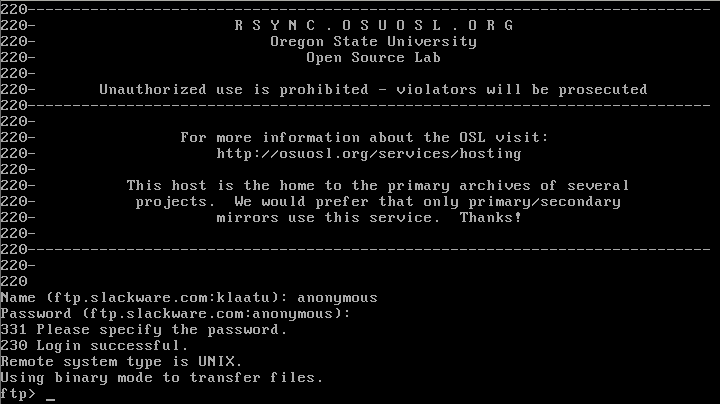

Slackware was created as a personal project to address the problems with SLS, lead by Patrick Volkerding. He had no intention to release Slackware, but it has become the oldest maintained distribution – currently used as the base for many operating systems. Decisions about the continued development of Slackware rest fully on the project's reluctant benevolent-dictator-for-life.

Slackware aimed to create the most "Unix-like" distribution and avoided editing modules written by other development teams. This created a versatile "vanilla" Linux experience that could be completely customized from scratch. By default, minimal software is installed and only the command line interface is available to interact.

Volkerding sought to create a more simple Linux experience, but referring to how the system operated and not how the system was used. Slackware had a steep learning curve and was by no means intended for someone new to the Linux ecosystem.

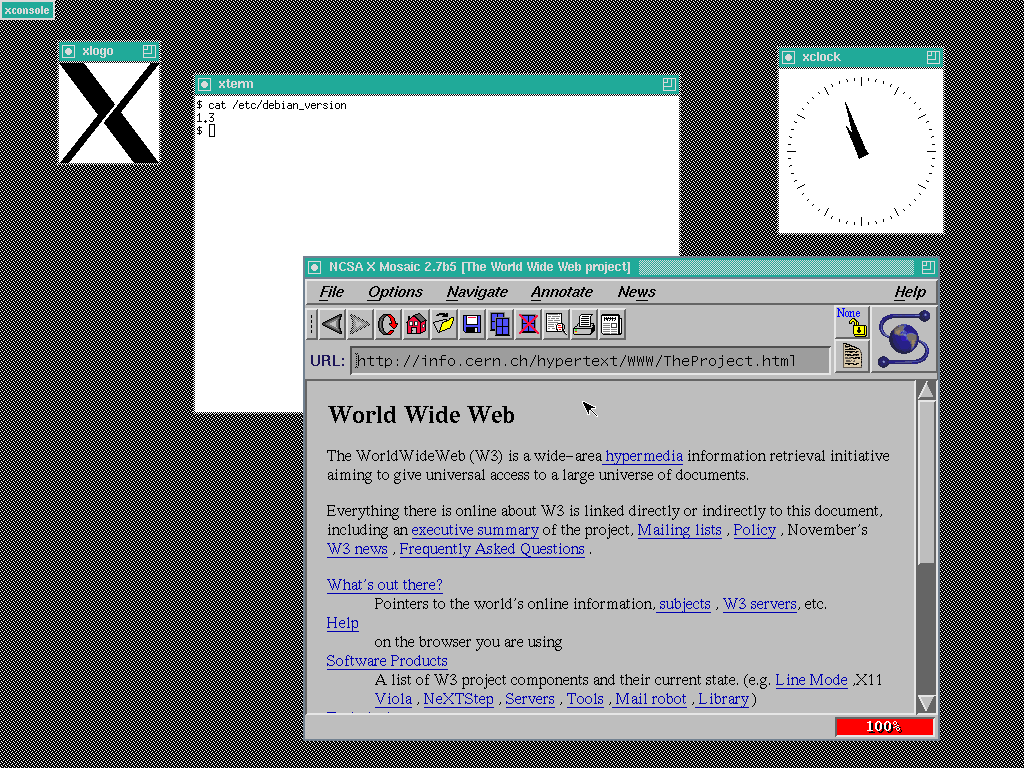

Released around the same time as Slackware, another Linux distribution emerged that sought to define simple in a different way. Similarly frustrated with SLS, Ian Murdock created the Debian project as a conscious response to it's perceived flaws.

Debian codenames are character names from the Toy Story film universe.

Debian v1.3 "Bo"

The Debian project is a volunteer-operated organization that operates entirely over the internet. Guided by an elected leader, their operation is governed by three foundational documents that outline their mission and vision:

|

Counter_1 |

This document outlines core principles of the project, as well as the developers who conduct its affairs.

|

| Counter_2 |

This document defines "free software" and sets the requirement for software that can be used to build the operating system. While similar to the GNU Manifesto, these guidelines specifically lay out avenues for a relationship with commercial '"non-free" software.

|

| Counter_3 |

This document explores the formal power structure, lying out the responsibilities of the Debian project leader and other organizational roles.

|

Debian has been developed according to principles similar to the GNU Project and had a short lived partnership. In contrast to the Free Software Movement, Debian proactively included important proprietary "non-free" software within their distro – such as firmware or drivers. Fundamentally, the organization wanted to remain open to commercial clients and potential relationships.

At the same time, Debian was conscious of the commercial Linux distributions that were forming – such as Red Hat. Concerned with the potential effects of profit on their project, they created the Social Contract to ensure the operating system remained open and free.

The Four Software Freedoms, while similar, were unknown to the Free Software Guideline authors. The modular nature of Linux allowed to work together regardless of project philosophy and organization. Within their criteria for compatible software, they defined software licenses they felt supported the spirit of the project.

Debian is now one of the most popular Linux distributions and many others have been created from it. As of 2025, there are almost 140 Linux-based operating systems that rely on Debian. It is leveraged almost everywhere – by governments, schools, corporations, non-profit organizations and even in space aboard the ISS to power their laptops.

Crowdsourcing Security

Security can be slippery to define because it encompasses so many different things. It manifests as a noun: in the moment, when we are safe from harm in our beds at the end of the day. Security also takes shape as a verb: occurring over time through our proactive measures to ensure our livelihood. It is both a feeling and a reality.

We contribute to our own feeling of safety by remembering to lock the door. The best protective measures don't occur in isolation, but as part of a holistic system that values and respects security. We build communities that impart onto us the feeling that we are supported. Now – and in the future – security is a mindset and relationship, not a task or a checklist that can be completed.

Security should not mean relying staying hidden, but instead remaining proactive. Throughout our lives, we must be careful to cultivate security by intentional design. We must act as an individual, as well as through our institutions and communities. Cybersecurity carries this vigilance into the digital systems we create to connect us.

Linux approaches security in a fundamentally different way than "closed-source" operating systems, like Windows and MacOS. By using proprietary software, end users must tacitly accept the security measures provided by the developers.

The source code used to create Linux, and almost all of its parts, is openly available on the internet for everyone to review. At first consideration, this may seem extremely insecure – to advertise all of the potential vulnerabilities to would be hackers.

Linus's Law, named after the creator of the Linux kernel, asserts that "given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow". The philosophy claims that the more independent developers are working on a project, including both volunteers and corporations, the greater your odds of finding bugs early. In the event of an emergent exploit, there are numerous perspectives searching for the fix.

While there have been no large-scale experiments or peer reviewed studies, empirical evidence can offer some clues. Popular open-source software had a higher ratio of big fixes than less popular projects by the same company. Relatedly, open-source GNU programs have demonstrated they're more reliable than their proprietary Unix counterparts.

We shouldn't allow ourselves to be lulled into false sense of security around open-source software. Simply making software code available to a brooader community does not guarantee that vulnerabilities will be immediately found and fixed. While a large community of people may use the software, there is no promise that they are providing feedback or code. This is why we must involve ourselves within our own security by making critical decisions.

A prominent and potent example within this discussion has been the Heartbleed security bug – which persisted in the code of a heavily utilized project for two years. A vulnerability within openssl, a project that securely encrypts a sizeable portiom of the Internet connections, was operated by fifteen unpaid volunteer developers.

In these cases, the eyeballs weren't really looking.

— Linux Foundation Director, Jim Zemlin

Linux focuses on a secure by design philosophy that builds a robust architecture from the ground up with conscious planning put into every layer. In order to crowdsource volunteers from their community, developers must consider from the start how their software might be exploited.

Transparency leads to faster response times and helps build community trust in the project. By presenting source code to developers and researchers, the community can take part in the software review process that has been repeatedly shown to address security issues. By receiving feedback from a diverse set of users and their unique hardware configurations, it's possible to crowdsource a stable foundation.

The Open Source Initiative aims to create a vendor-neutral environment that benefits from contributions from all sectors. High-profile institutions use Linux as well as individuals can lend their voices to open-source software. The Linux ecosystem has support built-in from a diversity of distributions – such as the community-supported Debian, the corporate-focused Fedora, or a hybrid-approach like Ubuntu. This can promote healthy competition and give people more choice about how to use their electronics.

Despite every precaution, exploits are bound to arise within a software program – especially as the code base grows larger, including code projects written and maintained by independent developers. By the security company Synopsys' estimates, over 80% of codebases have at least one vulnerability. On average, a codebase may have upwards of 150 exploits that have had documented solutions available for at least two years.

With proprietary software, these exploits are not always visible to researchers because the source code is not available publicly. The open-source ecosystem instead to build communities around their projects specifically dedicated to security. This enables clear and open communication about potential threats that make it difficult to keep ourselves and our families safe.

The Open-Source Security Foundation (known as OpenSSF) is operated by the Linux Foundation that is dedicated offering security testing for open projects. Through Security Score Cards, developers can quickly test their software and all of the open-source projects it uses to get an idea of vulnerabilities. By extension, they can increase transparency for this using the software by advertising their rating.

Debian – the operating system we'll be using – has created systems for crowdsourcing and responding to emergent threats. They employ a public bug tracking service that enables anyone to report errors and inconsistencies with the operating system. Developers, researchers and white hat hackers can work together to identify threats, separating them from relatively minor programming errors.

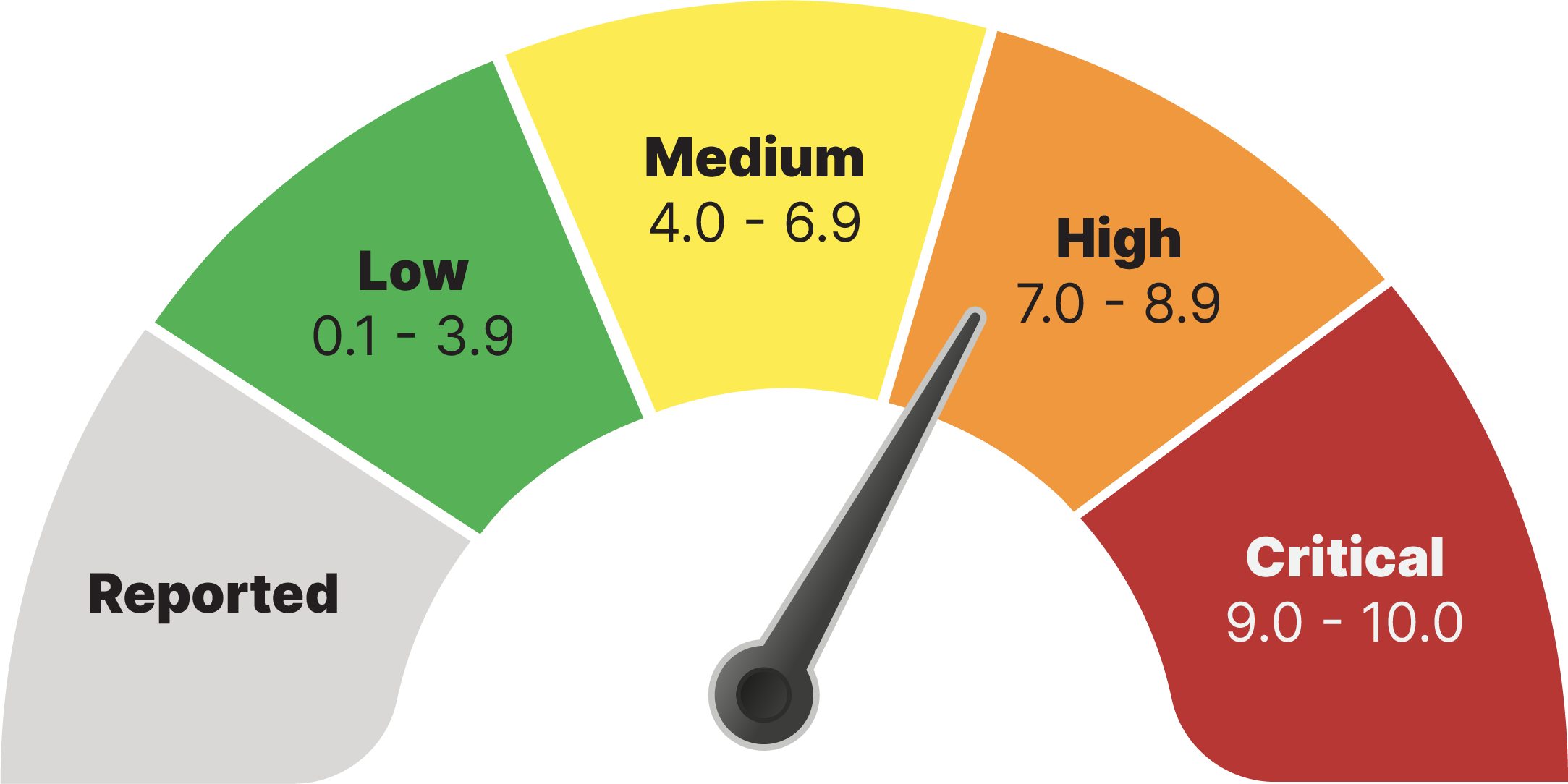

Once threats are identified, they are assessed for severity based on technical factors – including ease of use and potential impact. This rating, known as the Common Vulnerability Scoring System, and to offer a simple 1-to-10 metric for identified exploits. Once assessed, a prompt advisory is made public with information about the exploit and any possible protections until the exploit is formally fixed.

While an entirely volunteer-operated organization, Debian hosts a security team that proactively ensures the security of their current operating system version while working to resolve vulnerabilities. They maintain the processes and documentation to further harden Debian and make it even more difficult to exploit.