Building Community

The free and open software community is the culmination of the free software movement, the open source movement and numerous other independent developers who support software freedom. The GNU and Linux projects are the most extensive examples of free and open-source collaboration.

|

|

Through the collaborative creation of open software modules that fulfill precisely defined roles and tasks, Linux can be pieced together in many ways. This creates an expansive ecosystem where you are free to use the software that you choose. These large-scale experiments were not only technical, but social: how do you revolutionize the communication systems that go into decentralizing development?

Eric S. Raymond – a founder of the open-source movement – attributes Linux's success not to any particular technical innovation, but it's cooperative social systems and distributed power structure. Linux wasn't painstakingly handcrafted by a small group of privileged developers like other operating systems of the early digital age.

Linux evolved in a completely different way. From nearly the beginning, it was rather casually hacked on by huge numbers of volunteers coordinating only through the Internet. Quality was maintained not by rigid standards or autocracy but by the naively simple strategy of releasing every week and getting feedback from hundreds of users within days, creating a sort of rapid Darwinian selection on the mutations introduced by developers.

Melvin Conway – an early computer scientist and hacker – expressed a formative principle that is still relevant today: the structure of software will mirror the structure of the collective that built it. By embracing a new development model that relied on volunteers from around the world, a radical new form of asynchronous communication was necessary.

Open Collaboration

The Internet's capacity to build digital connections between two computers – and the people who used them – fundamentally changed the ways we can collaborate as Humans. We now had the power to communicate with little delay across vast distances and decisions could be made in near real-time.

This enabled people to work together directly, forming communities around mutual interests and shared goals. For the mutual benefit of the digital commons, communities produced valuable shared resources through processes that weren't primarily focused on generating profit.

Particularly notable success

Commons based peer production

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commons-based_peer_production

No softwareThese iscommunities and the projects that coalesce from within them are not owned by any one personparty. Each project has its own philosophy about their approach to design and can be formed.development.

The "very seductive" moral and ethical rhetoric of Richard Stallman and the Free Software Foundation fails (Raymond), he said, "not because his principles are wrong, but because that kind of language ... simply does not persuade anybody".[24]

Cathedral and the Bazaar, a living document by Eric S. Raymond, details his observations from within the early teams creating the Linux ecosystem. He examines the tension between bottom-up and top-down approaches to design. He likens these development styles to the ways that knowledge arises within a cathedral versus the bazaar.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Cathedral_and_the_Bazaar

The Cathedral and the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary (abbreviated CatB) is an essay, and later a book, by Eric S. Raymond on software engineering methods, based on his observations of the Linux kernel development process and his experiences managing an open source project, fetchmail. It examines the struggle between top-down and bottom-up design. The essay was first presented by Raymond at the Linux Kongress on May 27, 1997, in Würzburg, Germany, and was published as the second chapter of the same‑titled book in 1999.

The software essay contrasts two different free software development models:

- The cathedral model, in which source code is available with each software release, but code developed between releases is restricted to an exclusive group of software developers. GNU Emacs and GCC were presented as examples. The gnu project

- The bazaar model, in which the code is developed over the Internet in view of the public. Raymond credits Linus Torvalds, leader of the Linux kernel project, as the inventor of this process. Raymond also provides anecdotal accounts of his own implementation of this model for the Fetchmail project. Linux kernel

The essay's central thesis is Raymond's proposition that "given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow" (which he terms Linus's law): the more widely available the source code is for public testing, scrutiny, and experimentation, the more rapidly all forms of bugs will be discovered. In contrast, Raymond claims that an inordinate amount of time and energy must be spent hunting for bugs in the Cathedral model, since the working version of the code is available only to a few developers.

In it Raymond compares the Linux approach (the bazaar) to the GNU approach (the cathedral), and finds the former to be much more responsive to user needs. The essay eventually became a full-length book.

Raymond points to 19 "lessons" learned from various software development efforts, each describing attributes associated with good practice in open source software development:[3]

- Every good work of software starts by scratching a developer's personal itch.

- Good programmers know what to write. Great ones know what to rewrite (and reuse).

- Plan to throw one [version] away; you will, anyhow (copied from Frederick Brooks's The Mythical Man-Month).

- If you have the right attitude, interesting problems will find you.

- When you lose interest in a program, your last duty to it is to hand it off to a competent successor.

- Treating your users as co-developers is your least-hassle route to rapid code improvement and effective debugging.

- Release early. Release often. And listen to your customers.

- Given a large enough beta-tester and co-developer base, almost every problem will be characterized quickly and the fix obvious to someone.

- Smart data structures and dumb code works a lot better than the other way around.

- If you treat your beta-testers as if they're your most valuable resource, they will respond by becoming your most valuable resource.

- The next best thing to having good ideas is recognizing good ideas from your users. Sometimes the latter is better.

- Often, the most striking and innovative solutions come from realizing that your concept of the problem was wrong.

- Perfection (in design) is achieved not when there is nothing more to add, but rather when there is nothing more to take away. (Attributed to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry)

- Any tool should be useful in the expected way, but a truly great tool lends itself to uses you never expected.

- When writing gateway software of any kind, take pains to disturb the data stream as little as possible—and never throw away information unless the recipient forces you to!

- When your [configuration] language is nowhere near Turing-complete, syntactic sugar can be your friend.

- A security system is only as secure as its secret. Beware of pseudo-secrets.

- To solve an interesting problem, start by finding a problem that is interesting to you.

- Provided the development coordinator has a communications medium at least as good as the Internet, and knows how to lead without coercion, many heads are inevitably better than one.

Raymond had been a longtime contributor to open-source, in the Berkeley and GNU worlds.

At the start of the essay, Raymond writes

But I also believed there was a certain critical complexity above which a more centralized, a priori approach was required. I believed that the most important software (operating systems and really large tools like the Emacs programming editor) needed to be built like cathedrals, carefully crafted by individual wizards or small bands of mages working in splendid isolation, with no beta to be released before its time.

Linus Torvalds’s style of development—release early and often, delegate everything you can, be open to the point of promiscuity—came as a surprise. No quiet, reverent cathedral-building here—rather, the Linux community seemed to resemble a great babbling bazaar of differing agendas and approaches ... out of which a coherent and stable system could seemingly emerge only by a succession of miracles.

A distribution is largely driven by its developer and user communities. Some vendors develop and fund their distributions on a volunteer basis, Debian being a well-known example. Others maintain a community version of their commercial distributions, as Red Hat does with Fedora, and SUSE does with openSUSE.[116][117]

Many Internet communities also provide support to Linux users and developers. Most distributions and free software / open-source projects have IRC chatrooms or newsgroups. Online forums are another means of support, with notable examples being Unix & Linux Stack Exchange,[118][119] LinuxQuestions.org and the various distribution-specific support and community forums, such as ones for Ubuntu, Fedora, Arch Linux, Gentoo, etc. Linux distributions host mailing lists; commonly there will be a specific topic such as usage or development for a given list.

Although Linux distributions are generally available without charge, several large corporations sell, support, and contribute to the development of the components of the system and free software. An analysis of the Linux kernel in 2017 showed that well over 85% of the code was developed by programmers who are being paid for their work, leaving about 8.2% to unpaid developers and 4.1% unclassified.[122] Some of the major corporations that provide contributions include Intel, Samsung, Google, AMD, Oracle, and Facebook.[122] Several corporations, notably Red Hat, Canonical, and SUSE have built a significant business around Linux distributions.

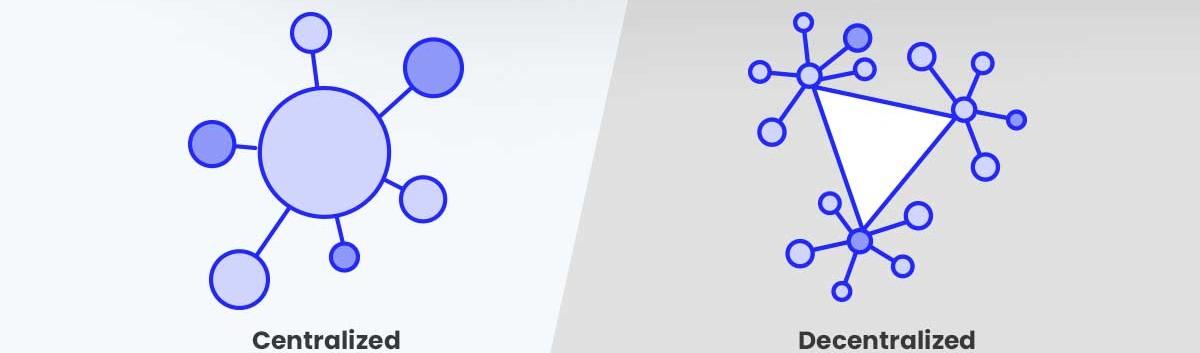

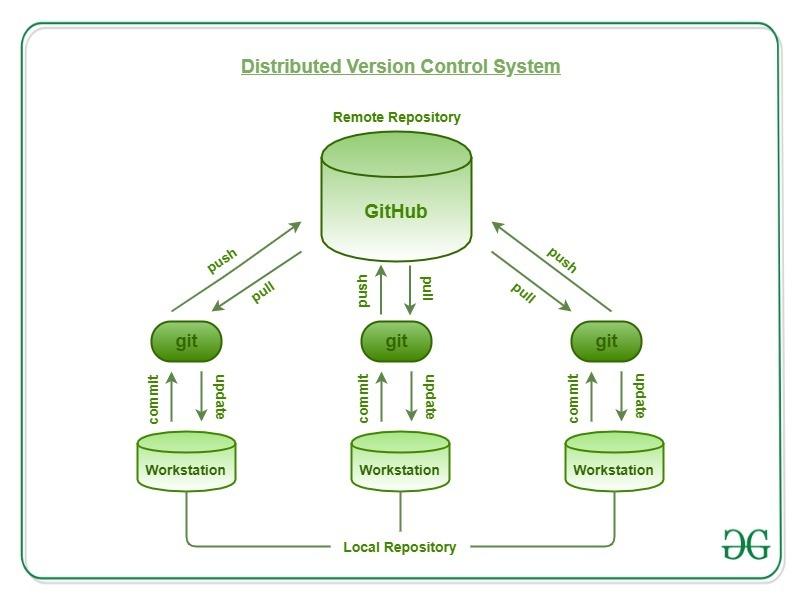

Decentralized Community

Decentralized development is a strategy where development tasks and decision-making are distributed across multiple, often geographically dispersed, contributors rather than being concentrated in a single location or team.

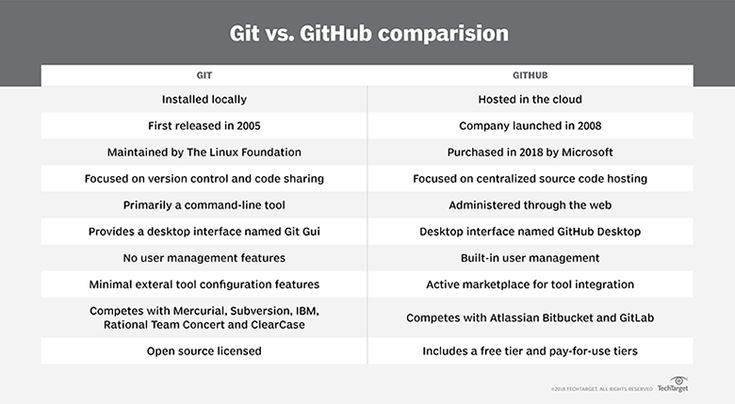

GitHub (/ˈɡɪthʌb/ ⓘ) is a proprietary developer platform that allows developers to create, store, manage, and share their code. It uses Git to provide distributed version control and GitHub itself provides access control, bug tracking, software feature requests, task management, continuous integration, and wikis for every project.[8]

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Git

Git is free and open-source software shared under the GPL-2.0-only license.

Git was originally created by Linus Torvalds for version control in the development of the Linux kernel.[14] The trademark "Git" is registered by the Software Freedom Conservancy, marking its official recognition and continued evolution in the open-source community.

It is commonly used to host open source software development projects.[10] As of January 2023, GitHub reported having over 100 million developers[11] and more than 420 million repositories,[12] including at least 28 million public repositories.[13] It is the world's largest source code host as of June 2023. Over five billion developer contributions were made to more than 500 million open source projects in 2024.[14]

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/GitLab

Gitlab is an open source alternative to GitHub that allows decentralized software hosting.

Today, Git is the de facto standard version control system. It is the most popular distributed version control system, with nearly 95% of developers reporting it as their primary version control system as of 2022.[15] It is the most widely used source-code management tool among professional developers. There are offerings of Git repository services, including GitHub, SourceForge, Bitbucket and GitLab.[16][17][18][19][20]

Git vs github

Repositories

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repository_(version_control)

a repository is a data structure that stores metadata for a set of files or directory structure.[1]

The main purpose of a repository is to store a set of files, as well as the history of changes made to those files.[3] Exactly how each version control system handles storing those changes, however, differs greatly.

In software engineering, a version control system is used to keep track of versions of a set of files, usually to allow multiple developers to collaborate on a project.

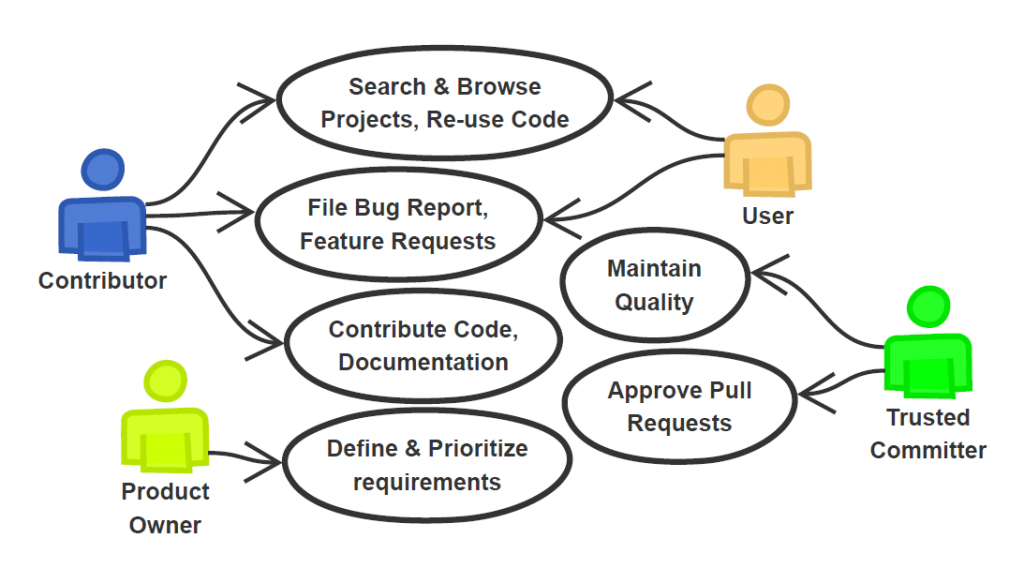

Trusted committer

Generally speaking, the Trusted Committer role is defined by its responsibilities, rather than by its privileges.

Compared to contributors, Trusted Committers have earned the responsibility to push code closer to production and are generally allowed to perform tasks that have a higher level of risk associated with them.

Maintainers

Repository maintainers are responsible for approving requests to push fixes to the repos they maintain. This involves checking that the bug is appropriate for inclusion into the targeted repo.

Contributors

Git (in a git repository) identifies authors and committers by email address. Github users can associate email addresses with their accounts. When a user's set of email addresses is found in the commit history of a github repo, github marks that user as a contributor.

Contributor — as the name implies—makes contributions to an InnerSource community. These contributions could be code or non-code artifacts, such as bug reports, feature requests, or documentation.

Contributors may or may not be part of the community. They might be sent by another team to develop a feature the team needs. This is why we sometimes also refer to Contributors as Guests or as part of a Guest Team. The Contributor is responsible for "fitting in" and for conforming to the community’s expectations and processes.

Collaborator

A user that has defined permissions in a github repo is marked as a collaborator. These permissions can vary and do not need to be the commit bit. A random org I am a member of shows the following options presently:

- read

- write

- admin

- issue triage

- non-admin manager

See also gh enterprise docs.

A user who has read-only access to a private repo should be marked as a collaborator, in my understanding.

A user who has permissions to a repo but no commits in that repo with any of email addresses associated with their github account would be a collaborator but not a contributor.

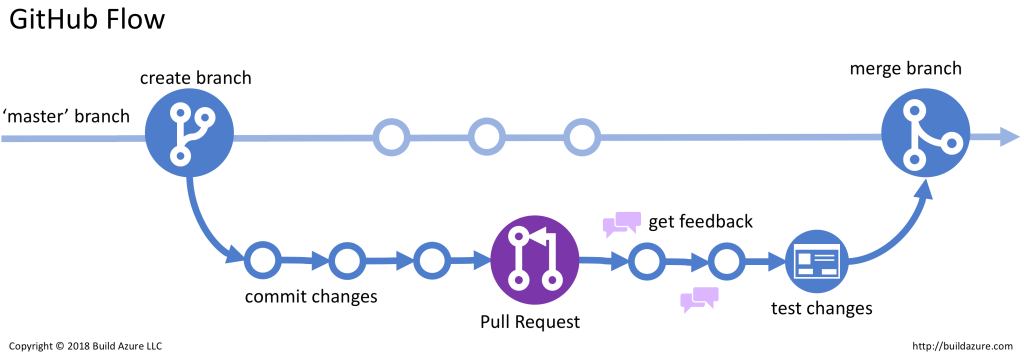

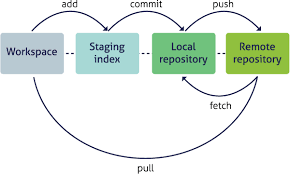

Branch - fork and merge

Branch

Branches are isolated within the same repository, allowing easier collaboration among team members who have access to the repository. Forks, on the other hand, create a completely separate copy of the repository, which is useful for outside contributors.

Fork

A fork is a new repository that shares code and visibility settings with the original “upstream” repository. Forks are often used to iterate on ideas or changes before they are proposed back to the upstream repository, such as in open source projects or when a user does not have write access to the upstream repository.

Merge

A branch is a parallel version of a repository. It is contained within the repository, but does not affect the primary or main branch allowing you to work freely without disrupting the "live" version. When you've made the changes you want to make, you can merge your branch back into the main branch to publish your changes.

Commits

A commit, or "revision", is an individual change to a file (or set of files). When you make a commit to save your work, Git creates a unique ID (a.k.a. the "SHA" or "hash") that allows you to keep record of the specific changes committed along with who made them and when. Commits usually contain a commit message which is a brief description of what changes were made.

Pull request

Pull requests are proposed changes to a repository submitted by a user and accepted or rejected by a repository's collaborators. Like issues, pull requests each have their own discussion forum.

Push

To push means to send your committed changes to a remote repository on GitHub.com. For instance, if you change something locally, you can push those changes so that others may access them.

Documentation

Documentation is any communicable material that is used to describe, explain or instruct regarding some attributes of an object, system or procedure, such as its parts, assembly, installation, maintenance, and use.[1]

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Software_documentation

Software documentation is written text or illustration that accompanies computer software or is embedded in the source code. The documentation either explains how the software operates or how to use it, and may mean different things to people in different roles.

- Requirements – Statements that identify attributes, capabilities, characteristics, or qualities of a system. This is the foundation for what will be or has been implemented.

- Architecture/Design – Overview of software. Includes relations to an environment and construction principles to be used in design of software components.

- Technical – Documentation of code, algorithms, interfaces, and APIs.

- End user – Manuals for the end-user, system administrators and support staff.

- Marketing – How to market the product and analysis of the market demand.

User documentation

Open source projects have three main types of documentation, each serving a specific purpose:

This is the developers' documentation. It delves into the codebase, explains APIs, and provides instructions for setting up development environments. README and API documentation are examples of technical documentation.

This type of documentation is meant for general users. Think user manuals that guide them through using the project and its features, such as installation guides, tutorials, troubleshooting guides, and FAQs.

3. Guidelines

These are the rules and roadmap for new contributors. Common types of guidelines in an open source project are:

- Contribution Guidelines: They usually explain how to submit code and bug reports and how to participate in the project, such as the contribution process and communication etiquette.

- Style Guides: They mainly guide contributors in maintaining coding and documentation consistency and quality.

Unlike code documents, user documents simply describe how a program is used.

In the case of a software library, the code documents and user documents could in some cases be effectively equivalent and worth conjoining, but for a general application this is not often true.

Typically, the user documentation describes each feature of the program, and assists the user in realizing these features. It is very important for user documents to not be confusing, and for them to be up to date. User documents do not need to be organized in any particular way, but it is very important for them to have a thorough index. Consistency and simplicity are also very valuable. User documentation is considered to constitute a contract specifying what the software will do. API Writers are very well accomplished towards writing good user documents as they would be well aware of the software architecture and programming techniques used. See also technical writing.

"The resistance to documentation among developers is well known and needs no emphasis."[10] This situation is particularly prevalent in agile software development because these methodologies try to avoid any unnecessary activities that do not directly bring value.

Documentation is an essential resource for developers, acting as a guidebook for understanding project features, APIs, configurations, and usage.

-

Enabling Adoption: Clear and well-structured documentation lowers the barrier to entry, making it easier for developers to understand and start using the open source project. It can facilitate adoption by providing installation instructions, usage examples, and integration guides.

-

Empowering User Satisfaction: Well-documented projects lead to better user experiences. Comprehensive documentation ensures that users can effectively leverage the project's capabilities, troubleshoot issues, and find answers to their questions, ultimately increasing user satisfaction.

-

Encouraging Collaboration: Documentation is the foundation for collaboration within the open source community. When contributors have access to accurate and up-to-date documentation, they can effectively contribute code, submit bug fixes, and improve the project's overall quality.

Best Practices for Documentation in Open Source

One of the challenges of documentation–or any form of long writing–is creating a well-organized document that doesn’t give too much information but empowers the user to get started without having a lack of understanding. Here are some tips for creating good documentation:

https://dev.to/opensauced/the-role-of-documentation-in-open-source-success-2lbn

Part of the Community

Why do people contribute?

The Debian Project has an influx of applicants wishing to become developers.[205] These applicants must undergo a vetting process which establishes their identity, motivation, understanding of the project's principles, and technical competence.[206] This process has become much harder throughout the years.[207]

Debian developers join the project for many reasons. Some that have been cited include:

- Debian is their main operating system and they want to promote Debian[208]

- To improve the support for their favorite technology[209]

- They are involved with a Debian derivative[210]

- A desire to contribute back to the free-software community[211]

- To make their Debian maintenance work easier[212]

Debian developers may resign their positions at any time or, when deemed necessary, they can be expelled.[29] Those who follow the retiring protocol are granted the "emeritus" status and they may regain their membership through a shortened new member process.[213]

Debian has made efforts to diversify and have members represented from the community. Debian Women in 2004 was established with the aim of having more women involved in development. Debian also partnered with Outreachy, which offers internships to individuals with underrepresented identities in technology.[214][215]

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diversity_in_open-source_software

Researchers and journalists have found a higher gender disparity and lower racial and ethnic diversity in the open-source-software movement than in the field of computing overall, though a higher proportion of sexual minorities and transgender people than in the general United States population. Despite growing an increasingly diverse user base since its emergence in the 1990s, the field of open-source software development has remained homogeneous, with young men constituting the vast majority of developers.

Since its inception in the 1990s, as open-source software has continued to grow and offer new solutions to everyday problems, an increasingly diverse user base began to emerge. In contrast, the community of developers has remained homogeneous, dominated by young men.[3]

In 2017, GitHub conducted a survey named the Open Source Survey, collecting responses from 5,500 GitHub users. Among the respondents, 18% personally experienced a negative interaction while working on open-source projects, but 50% of them have witnessed such interactions between other people. Dismissive responses, conflict, and unwelcoming language were respectively the third, fourth, and sixth most cited problems encountered in open-source.[4]

Another study from 2017 examined 3 million pull requests from 334,578 GitHub users, identifying 312,909 of them as men and 21,510 as women from the mandatory gender field in the public Google+ profiles tied to the same email addresses as these users were using on GitHub. The authors of the study found code written by women to be accepted more often (78.6%) than code written by men (74.6%). However, among developers who were not insiders of the project, women's code acceptance rates were found to drop by 12.0% if gender was immediately identifiable by GitHub username or profile picture, with only a smaller 3.8% drop observed for men under the same conditions. Comparing their results to a meta-analysis of employment sex discrimination conducted in 2000, the authors observed that they have uncovered only a quarter of the effect found in typical studies of gender bias. The study concludes that gender bias, survivorship and self-selection bias, and women being held to higher performance standards are among plausible explanations of the results.[5]

The gender ratio in open source is even greater than the field-wide gender disparity in computing. This was found by a number of surveys:

- A 2002 survey of 2,784 open-source-software developers found that 1.1% of them were women.[7]

- A 2013 survey of 2,183 open-source contributors found that 81.4% were men and 10.4% were women.[8] The survey included both software contributors and non-software contributors and found that women were much more likely to be non-software contributors.[9]

- In the GitHub's 2017 Open Source Survey 95% respondents identified as men and only 3% as women,[4] while in the same year about 22.6% of professional computer programmers in the United States were female according to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics.[10][11]

In an 2013 article for the NPR, journalist Gene Demby considered Black people and Latinos to be underrepresented in the open source software development.[12]

- In the GitHub's 2017 Open Source Survey the representation of immigrants, from and to anywhere in the world, was 26%.[4]

- In the same survey, 16% of respondents identified as members of ethnic or national minorities in the country where they currently live,[4] while according to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, Black, Asian, and Latino people accounted for a total of about 34% of programmers in the United States in 2017.[10][11]

Among the respondents of GitHub's 2017 Open Source Survey 1% identified as transgender, 1% as non-binary, and 7% as lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, or another minority sexual orientation,[4] while according to a Gallup poll in conducted in the same year 4.1% of the United States population identify as LGBT.[13][11] A 2018 survey of software developers conducted by Stack Overflow found that out of their sample of 100,000, 6.7% in total identified as one of "Bisexual or Queer" (4.3%), "Gay or Lesbian" (2.4%), and "Asexual" (1.9%), while 0.9% identified as "non-binary, genderqueer, or gender non-conforming".[14]

Large personalities in open source and complicated views

Eric s Raymond

Linus torvalds

The "very seductive" moral and ethical rhetoric of Richard Stallman and the Free Software Foundation fails (Raymond), he said, "not because his principles are wrong, but because that kind of language ... simply does not persuade anybody".[24]

How Can I Contribute?

How to contribute to open source software projects

Financial Support

Donations

Sponsorship

Non profit funds

Open Collective is a crowdfunding platform focused on grassroots groups. It enables organizations, communities, and projects to get a legal status and raise funding through subscription or one time payment. It's particularly favoured by open source projects.[1] It currently hosts funding for thousands of open-source communities.[2]

https://www.spi-inc.org/donations/

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Software_in_the_Public_Interest

Software in the Public Interest, Inc. (SPI) is a US 501(c)(3) non-profit organization domiciled in New York State formed to help other organizations create and distribute free open-source software and open-source hardware. Anyone is eligible to apply for membership, and contributing membership is available to those who participate in the free software community.

https://www.pledge.to/women-in-linux-4579

Community Support

Documentation

Feedback

Finding forums, chat apps, websites

Forums and mailing lists

Polls and feedback

Emergent strategy

Irc chatroom

I offer, from this defensive and sacred place, a protocol for those who are most comfortable approaching movements from a place of critique, AKA, haters.

1. Ask if this (movement, formation, message) is meant for you, if this serves you.

2. If yes, get involved! Get into an experiment or two, feel how messy it is to unlearn supremacy and repurpose your life for liberation. Critique as a participant who is shaping the work. Be willing to do whatever task is required of you, whatever you are capable of, feed people, spread the word, write pieces, make art, listen, take action, etc. Be able to say: ‘“T invest my energy in what I want to see grow. I belong to efforts I deeply believe in and help shape those.”

3. Ifno, divest your energy and attention. Pointing out the flaws of something still requires pointing at it, drawing attention to it, and ultimately growing it. Over the years I have found that when a group isn’t serving the people, it doesn’t actually last that long, and it rarely needs a big takedown—things just sunset, disappear, fade away, absorb into formations that are more effective. If it helps you feel better, look in the mirror and declare: “There are so many formations I am not a part of—my non-participation is all I need to say. When I do offer critique, itis froma space of relationship, partnership, and advancing a solution.”

4. And finally, 1f you don’t want to invest growth energy in anything, just be quiet. If you are not going to help birth or raise the child, then shhhhh. You aren’t required to have or even work towards the solution, but if you know a change is needed and your first instinct when you see people trying to figure out how to change and transform is to poop on them, perhaps it is time you just hush your mouth.

Development Support

Feature requests

Pull requests

Contributions