Building Community

The free and open software community is the culmination of the free software movement, the open source movement and numerous other independent developers who support software freedom. The GNU and Linux projects are the most extensive examples of free and open-source collaboration.

|

|

Through the collaborative creation of open software modules that fulfill precisely defined roles and tasks, Linux can be pieced together in many ways. This creates an expansive ecosystem where you are free to use the software that you choose. These large-scale experiments were not only technical, but social: how do you revolutionize the communication systems that go into decentralizing development?

Eric S. Raymond – a founder of the open-source movement – attributes Linux's success not to any particular technical innovation, but it's cooperative social systems and distributed power structure. Linux wasn't painstakingly handcrafted by a small group of privileged developers like other operating systems of the early digital age.

Linux evolved in a completely different way. From nearly the beginning, it was rather casually hacked on by huge numbers of volunteers coordinating only through the Internet. Quality was maintained not by rigid standards or autocracy but by the naively simple strategy of releasing every week and getting feedback from hundreds of users within days, creating a sort of rapid Darwinian selection on the mutations introduced by developers.

Melvin Conway – an early computer scientist and hacker – expressed a formative principle that is still relevant today: the structure of software will mirror the structure of the collective that built it. By embracing a new development model that relied on volunteers from around the world, a radical new form of asynchronous communication was necessary.

Open Collaboration

The Internet's capacity to build digital connections between two computers – and the people who used them – fundamentally changed the ways we can collaborate as Humans. We now had the power to communicate with little delay across vast distances and decisions could be made in near real-time.

This enabled people to work together directly, forming communities around mutual interests and shared goals. For the mutual benefit of the digital commons, communities produced valuable shared resources through processes that weren't primarily focused on generating profit.

|

Particularly notable examples include Wikipedia, open-source software and open hardware. These communities and the projects that coalesce from within them are not owned by any one party. Each project has its own philosophy about their approach to design and development.

The Cathedral and the Bazaar, a living document by Eric S. Raymond, details his observations from within the early teams creating the Linux ecosystem. He examines the tension between bottom-up and top-down approaches to design within software. He likens these styles to the ways that knowledge arises within a cathedral versus the bazaar.

Essay Excerpt

But I also believed there was a certain critical complexity above which a more centralized, a priori approach was required. I believed that the most important software (operating systems and really large tools like the Emacs programming editor) needed to be built like cathedrals, carefully crafted by individual wizards or small bands of mages working in splendid isolation, with no beta to be released before its time.

Linus Torvalds’s style of development—release early and often, delegate everything you can, be open to the point of promiscuity—came as a surprise. No quiet, reverent cathedral-building here—rather, the Linux community seemed to resemble a great babbling bazaar of differing agendas and approaches ... out of which a coherent and stable system could seemingly emerge only by a succession of miracles.

– The Cathedral and The Bazaar

|

Church |

The Cathedral These open-source projects release their source code once it has been finalized, but it is not available to the general public while in active development. This restricts who has the privilege to make changes to the underlying source code to an exclusive group.

The GNU project often uses this philosophy.

|

| Storefront |

The Bazaar These open-source projects make their source code completely available on the Internet throughout the entire development process. Everyone has access to the source code, but making modifications to it requires oversight by the project.

The Linux kernel uses this philosophy. |

A Linux distribution is primarily powered by its community – which can take many different forms. Debian is a well-known example supported by the public on a volunteer basis by global developers. Some distributions like Fedora are community-maintained operating systems that were split off from corporate-focused Linux builds.

While Linux is generally free-of-charge, technology companies contribute to the continued development of the ecosystem. An estimated 85% of the modern Linux kernel was written by developers who were paid for their work.

There is an array of digital communities that support Linux users and developers, each with a specific purpose or mission. Linux Questions and Stack Exchange are online discussion forums that can provide general Linux support. Many open-source projects have their own forum as well as IRC chatrooms, mailing list and newsgroup.

Decentralized Development

Rather than concentrating power within a single location or team, decentralization distributes tasks and decision-making across multiple contributing members. This is a flexible and efficient option for collaborating, but requires constant communication and robust planning if it's going to succeed.

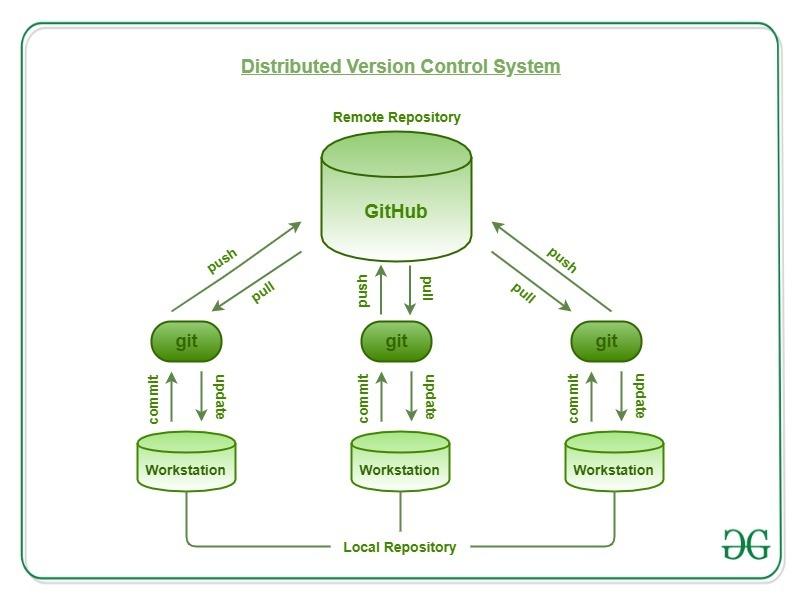

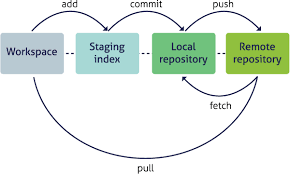

The concept of version control is heavily leveraged by open-source software projects. This has led to powerful tools that can keep track of changes in the source code made by hundreds of potential contributors. This creates a central repository for critical project files with strict processes in place for modifying them.

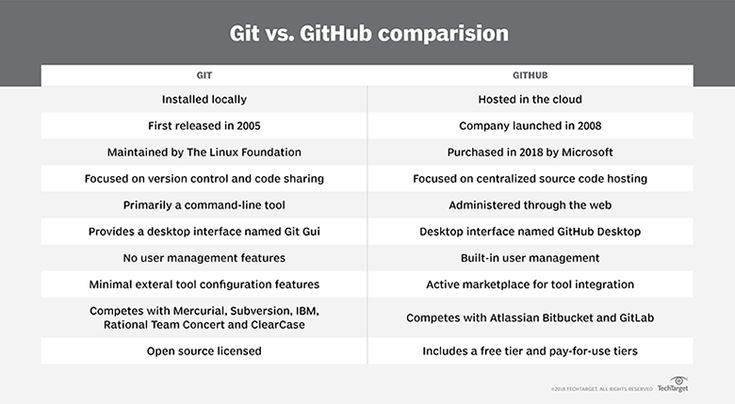

Git is a program originally created by Linus Torvalds in 2005 as version control for the Linux kernel. It is now the official standard over 90% of developers consider it to be their primary tool for the job. In essence, Git downloads an exact replica of the central repository to your computer.

With the source code on your hard drive, you can compile the program for yourself from scratch. As a developer, you can make alterations and upload them back to the central server. This helps ensure that a developer can work on one section of the program without getting in anyone else's way – while also leaving a trail of the changes.

|

|

While Git is primarily a command-line utility, there are many online repositories that work with Git – but the most popular is by far GitHub. Owned by Microsoft, it is the largest online repository of open source-code with millions of developers and projects. GitLab is an open-source and decentralized alternative that can be self-hosted.

In addition to acting as a shared Git repository, these platforms provide community development tools. This includes bug tracking, feature requests, task management, a forum and a wiki for documentation. Developers can configure "continuous integration and continuous delivery" where pre-programmed tests are performed on source code before it is automatically compiled.

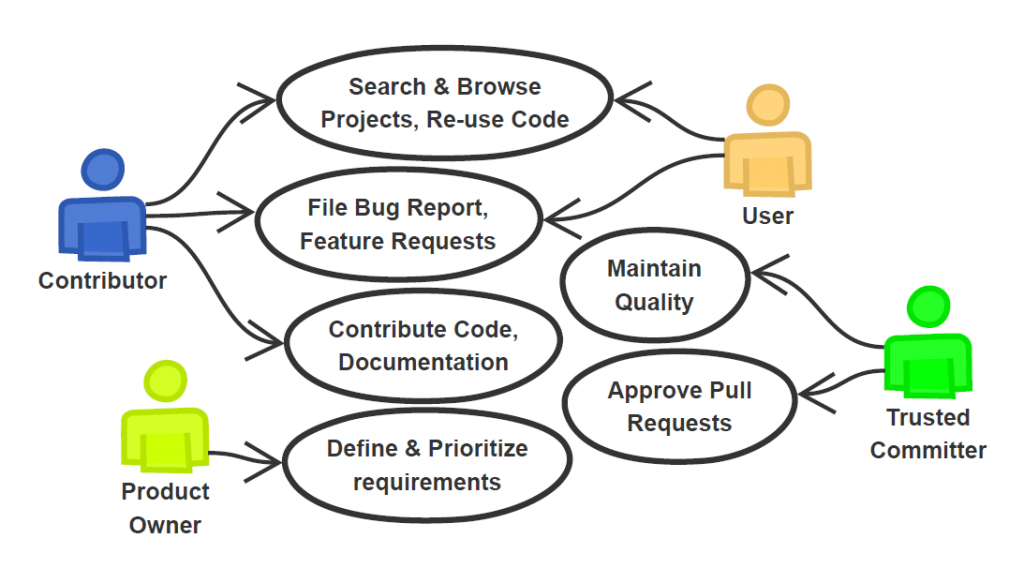

When using a public software repository platform, there are roles that get fulfilled within each project. While there can only be one formal owner of the project, they are free to create granular permissions for who can edit what. Most projects hosted on a public source code repository maintain these general conventions when it comes to collaboration.

|

Domino_mask |

Anonymous Unless a software project has been intentionally marked as private, the source code is freely available for download by anyone who accesses the repository even if they haven't logged in. |

|

person |

User This is any person who has an account on the platform with a verified email. Each project can configure how unaffiliated users are allowed to interact with the source code. Open-source software debelopers often value diverse perspectives from every day users and explicitly request feedback. |

|

deployed_code_account |

Collaborator This is any person that a software project has explicitly chosen to give affiliation status. This can offer fine tuned control to specific developers and provide blanket access to all collaborators. In the case of a private project, this can be used to offer exclusive access to source code. |

| Person_edit |

Contributor Once a verified user has submitted a change and it's accepted, they are considered a contributor within that project. Before proposing changes, each user must follow the rules and integrate themselves into the community. These contributions are not limited to source code, but also include stewardship responsibilities – such as bug reports, feature requests and documentation writing. |

| how_to_reg |

Trusted Member This role can vary widely between projects and is often defined more by their responsibilities than their privileges. While an average contributor can suggest changes, these project members are often the ones in charge of actuating them. These tasks often have a greater degree of risk involved and require earning the respect of the community. |

| engineering |

Maintainer This entity has the significant responsibility of overseeing the project and it's community. While there can only be one primary maintainer, this can represent a collective or organization. They perform technical tasks as well as maintain the project's direction.

|

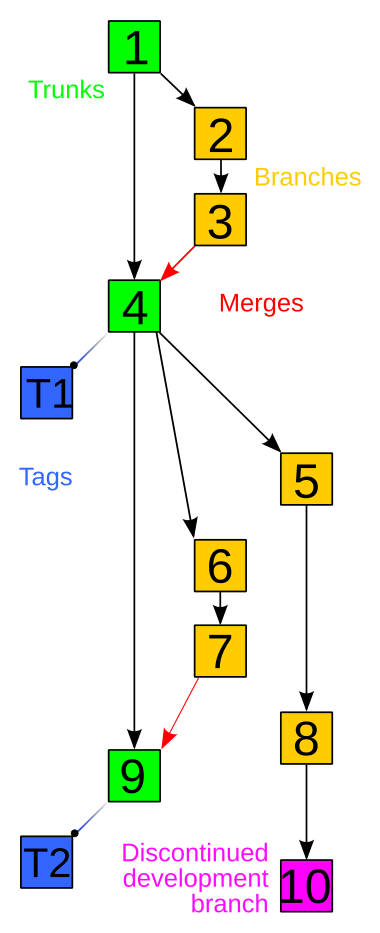

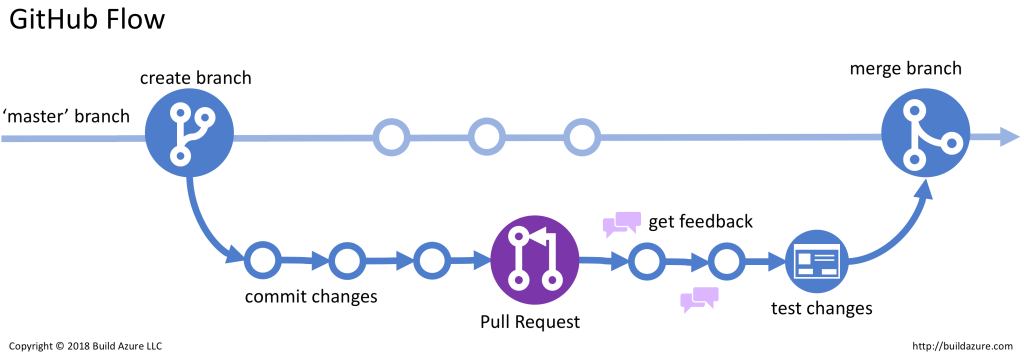

Project members work together to complete work within the main repository containing all the project's source files. This software development process is likened to a tree – with the collective source code called the main trunk.

As existing bugs or new features are explored, new branches in the tree can be split from the source code – essentially creating two isolated versions of the same software. This is often done when developing new versions of a program to make it easier to keep track of differences over time.

|

call_split |

This is an isolated copy of the source code that makes it easier for developers to collaborate on changes without risking damage to the trunk. These help to keep track of what was changed, by who, and for what reason. These exist within a project to facilitate collaboration and coordinate development.

|

| call_merge |

Once changes within a branch are finalized and tested to ensure stability, then can be merged back into the main trunk. This allows all software development loose ends to be addressed before creating a final release of the software trunk. |

| Flowchart |

This is a completely new repository – under new ownership – that is a complete replica of another existing repository. This can happen for a variety of reasons ranging from personal modifications to differing decisions among the development team. Repository forks allow anyone to modify software to their needs and propose changes back to a project they are not a developer on. |

Developers can commit changes to files within each branch to test put features and make sure everything works as expected. Large software projects – like an operating system – can go many branches deep to explore specific topics.

The community can discuss development at many granular levels. When changes are complete, these branches can be consolidated and merged back into the main trunk. This can include resolving any conflicting changes in the source code. When changes are finalized, the software can be released for general production usage.

|

Commit |

This is a formal change to source code files on your local repository that are given a unique identification number and maintain a narrative about its history. This builds a foundation of accountability by tracking who made what changes to files when. Traditionally, these contain a message from the developer about their changes and the reasoning behind it. |

| cloud_upload |

Once you have finalized your commit, the changes can be pushed upstream to the central repository so they can be accessed by everyone.

|

| Cloud_download |

When first acquiring the source files from a project's repository, Git on your computer will pull the code from the repository. This allows you to modify the files and compile the program yourself from scratch.

As a part of the project, you can often commit and push the files directly back to the repository. When you are not affiliated with the project, you can create your own fork and communicate with the parent project about your proposed changes. From there, they can perform a pull request to merge the new code created in your personal fork.

|

This enables every developer to quickly create their own environment to experiment with code, compile the program and test for any bugs. By providing redundant layers of communication, a diverse collective of developers can keep in communication about emerging changes to the software.

Documentation

Git is a fantastic tool for facilitating collaboration among a diverse development team on complex coding problems. However, it doesn't do much to help out someone looking to use the software for the first time – or a developer looking to get involved.

Contributing to open source is not only a technical challenge but equally a social challenge. Documentation is needed to enable remote asynchronous collaboration, which is how communities work.

If everything is stuck inside of people's heads, that's going to create an atmosphere of confusion, frustration, and inefficiency. Documentation isn't just essential for code; it's also a guide to understanding each project's cultural and communication norms.

— Nuritzi Sanchez, senior manager

What we can independently learn about an open-source project greatly informs our ability to use it. In the long term, it affects our ability to become a part of the community surrounding it. While Git manages how the software is created, documentation ventures to cover just about everything else – like what it does, how it works and why you would use it.

Software documentation, as the name implies, relates specifically to software projects. These are foundational resources that enumerate, extrapolate, explain and educate about each part, procedure or platform that keep it functional – like it's assembly, installation, setup, use and maintenance. Since it's coverage is expansive, documentation is often split into self-contained – but intertwined – parts.

|

Support |

User Documentation While intended for a general audience, this resource can explore the software from multiple distinct perspectives – such as users, systems administrator and support staff.

This describes the features of a program and explores how users can fully leverage them. Consider it the contract detailing what the software does. Documentation can fulfill using guides, tutorials, troubleshooting and frequently asked questions.

While they are not inherently designed in a specific way, the overall goal to create a resource that is intuitive and accessible – clearing more confusion than it creates. Most incorporate an index for exploring defined concepts or sections. |

|

Engineering |

Technical Documentation Intended primarily for developers, this resource helps to grasp how the programs works internally. This covers the logic behind algorithms, explains how to leverage their API, and details emergent software systems that power the program. Technical documentation may be available on its own wiki or integrated directly into the source code.

|

| Volunteer_activism |

Contribution Guidelines Open-source software projects often come with information about how you can help contribute to the project. This generally explores the process and guidelines for becoming a contributor, such as how to submit bug reports and feature requests as well as rules and etiquette for communication.

|

Documentation is an essential resource for fully leveraging software. When well-executed, it lowers the barrier to entry and offers entrance into a more connected community. Comprehensive coverage can improve the overall experience with a safety net for troubleshooting problems and finding answers. When possible, it is details how we can give back to the free and open-source community.